Roman Catholic Iconography and Bare-Breasted Women

The influence of Catholic iconography weighs heavy in my personal repertoire of pictographic languages. Pair that with bare-breasted women, and you get a unique recipe for feminist art.

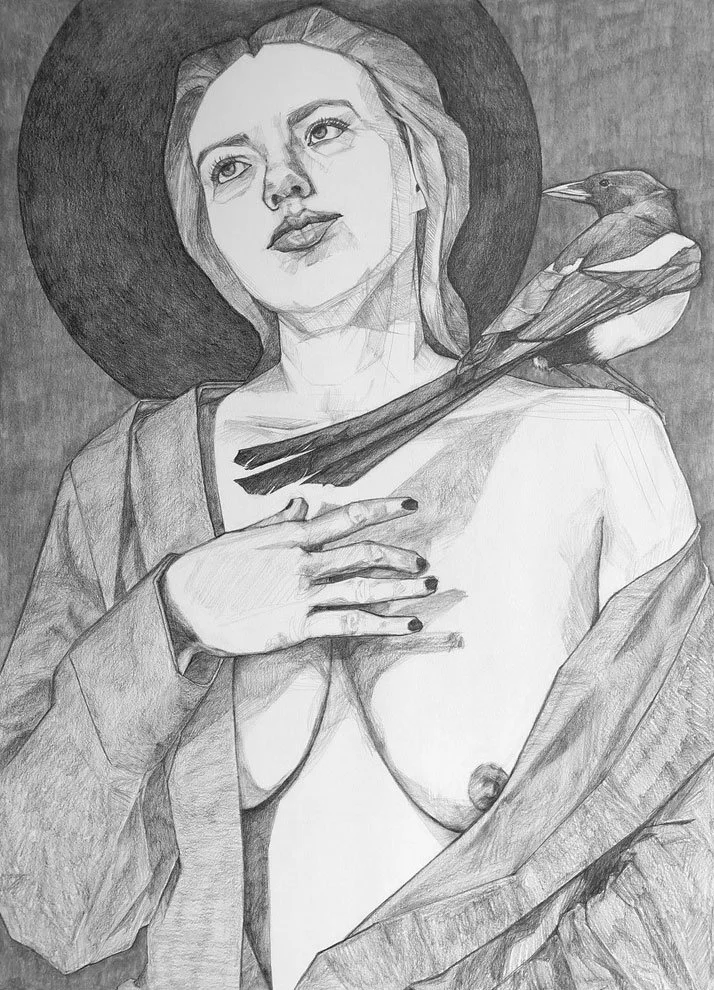

“Our Lady of Sorrow,” graphite on paper, 18x24 inches, 2022.

Bare-Breasted Women

In 1622, a French regent named Marie de’ Medici commissioned artist Peter Paul Rubens to paint her portrait wearing equestrian general attire and was depicted as the ancient Roman goddess of war, Bellona. In the painting Marie de’ Medici is depicted standing tall, with one breast bared.

At the time, a recurring question in France was the ability of women to govern. Ruling families followed the Salic Law, which allowed only men to inherit the throne, or otherwise, the power to rule. However, this law was challenged in practice by Marie de’ Medici and other feminist female rulers.

The portrait that Rubens painted was a nod to the mythical warrior women - the ancient Amazons, a society in Greek and Roman legend that challenged the patriarchal order - and reflected an emerging concept of “Femme Forte,” or a strong female leader. Think: the mythical birthplace of Wonder Woman.

Painting of Marie de’ Medici as Bellona, by Peter Paul Rubens, 1622-1625, oil on canvas. Photo from Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, written by Mary D. Garrard.

Marie de’ Medici’s daughter-in-law, Anne of Austria, continued to fortify the concept of Femme Forte during her rule succeeding Marie de’ Medici, and the two queens used the king’s money to commission and patron feminist artist, Artemisia Gentileschi. In the late 1610s, anti-feminist literature surged throughout France, and these woman were defiant to it.

Artemisia was the foremost female Baroque painter (there were very few, and Artemisia was taught to paint by her father, who was also a painter). Painting was a respected career in the 1600s and was a trade dominated predominantly by men, so it is likely that Artemisia would never have been taught to paint if it was not for her father. Women were considered to be the property of their fathers, and once married, the property of their husbands. Their dowry would go straight from father to husband and the woman would have no claim or use of her own money.

Despite the education her father gave her, Artemisia largely despised him. As a young woman she was raped by her father’s friend who was also a painter, under the guise that he was to be giving her painting lessons, as well. The matter was taken to court by Artemisia’s father, and the friend was punished by law and ordered to give reparations, not because of the assault he committed against Artemisia, but for the “damage” that was incurred to Artemisia’s father’s property (his daughter).

After the trial, Artemisia was from then on publicly viewed as sexually promiscuous and of low virtue. For that, she never forgave her father and resented him for taking the assault to trial. When she was able, she made her own pathway and career as a painter, seldom speaking to her father and eventually abandoning the husband to which she and her dowry were betrothed.

For that reason, it makes sense that the two powerful female leaders - Marie de’ Medici and Anne of Austria - would begin a patronage with Artemisia upon learning about her and her work, especially in a time when most court painters were men.

Anne of Austria eventually commissioned a painting from Artemisia Gentileschi, and Artemisia depicted her as Minerva, the ancient Greek and Roman goddess of war, known for fighting on behalf of just causes. Below, the laurel crown depicted, as well as the olive branch she holds, are not symbolism typically associated with Minerva, but rather with French royalty. Her spear, shield, and bare breasts indicate the warrior symbolism of Minerva, also harkening back to the ancient Amazons.

Painting of Anne of Austria as Minerva, by Artemisia Gentileschi, 1630-1635, oil on canvas. Photo from Artemisia Gentileschi and Feminism in Early Modern Europe, written by Mary D. Garrard.

The story of these portraits and their patronage is interesting to me because they stand out by depicting the power of women through the use of nudity (bare breasts), rather than subjectification, and I am interested in exploring this concept more thoroughly through my art.

Enter: Roman Catholic Iconography

The influence of Catholic iconography weighs heavy in my personal repertoire of pictographic languages. Despite growing up Roman Catholic, I no longer identify with the religion. However, I hold an affinity towards the iconography, having grown up Polish in a predominantly Polish community within the United States - an ethnic group where the primary religion is Roman Catholic - and that affinity shows itself in my work.

In the graphite portrait titled Our Lady of Sorrow found at the beginning of this post, there is heavy Catholic symbolism. I used myself as a model, and there is a nimbus drawn around the head within the portrait; a nimbus is a halo or light surrounding the head of a spiritual being, or saint, and is used heavily in Roman Catholic imagery. The eyes are cast upward, suggesting prayer.

The use of symbolism within my artwork, and likely within the work of other artists, is more fluid and marked by subconscious flow more than what one might think. However, I will say that the portrait Our Lady of Sorrow came out of a time of mourning, and with mourning often comes the sudden comfort from the idea of the existence of a higher power, even if you’ve never believed.

Some of the imagery is new imagery, symbolic of where I am located now and what I see daily. After moving to Montana, I became very taken with the magpie bird and its symbolism, given the opportunity for frequent sightings of the bird across the plains. There is a magpie found perched on the left shoulder within the drawing, and this symbolism is derived directly from the traditional nursery rhyme about magpies. According to old superstition, the number of magpies seen indicates if one will have good or bad luck:

One for Sorrow

Two for Joy

Three for a Girl

Four for a Boy

Five for Silver

Six for Gold

Seven for a Secret

Never to be told…

Eight for a Wish

Nine for a Kiss

Ten for a Bird

You must not miss.

…and so the use of the single magpie denotes sorrow, in this case, from loss.

Lastly, the garment draping within the drawing is meant to be similar to that of the garment draping seen in images of saints and holy people. Except for here, like the paintings of Artemisia Gentileschi, I have chosen to leave the chest bare. Similarly to her paintings, the bare chest represents strength, fortitude, and Femme Forte; the powerful woman.